Video games present us with a unique experience unlike that of any other form of media. Video games combine elements of film, music and art to create a profound, interactive experience for the gamer. While video games have been a fairly recent development compared to that of film and music, the genre is quickly gaining prominence in the entertainment world, earning billions of dollars in sales annually. What makes the experience of video games truly unique is the relationship between the player and the simulated geography within a game. Not only do video games facilitate this relationship, but each game approaches it differently, leading to hundreds of ways of experiencing the concept of simulated space. For the purpose of this paper I will be discussing some of the geographic concepts learned in class and in the readings, as well as relating them to some video games of my own choosing.

The definitions of place and space are interesting when chosen to be applied to video games. Cresswell’s definitions of place and space are geographical in nature while Nitsche’s are more conducive to the nature of video games (though drawn from Lefebvre) . Cresswell defines place as material and having historical as well as personal significance. A place is fixed in space, which is the abstract concept of moving through a place. Space is everything that place is not. Cresswell states that particularly successful media conveys a profound sense of place, as if “we have been there before.” Lefebvre’s definitions of “absolute space” and “social space” are essentially Cresswell’s definitions of space and place, respectively. Nitsche uses the concepts of absolute and social space to put forth ideas about place and space in gaming. Nitsche states that “video games are social spaces understood as ‘narrative landscapes.’” What Nitsche is trying to say here is that gamers create their own sense of place through their interactions with virtual space. These interactions create a narrative unique to that player.

The definitions of place and space are interesting when chosen to be applied to video games. Cresswell’s definitions of place and space are geographical in nature while Nitsche’s are more conducive to the nature of video games (though drawn from Lefebvre) . Cresswell defines place as material and having historical as well as personal significance. A place is fixed in space, which is the abstract concept of moving through a place. Space is everything that place is not. Cresswell states that particularly successful media conveys a profound sense of place, as if “we have been there before.” Lefebvre’s definitions of “absolute space” and “social space” are essentially Cresswell’s definitions of space and place, respectively. Nitsche uses the concepts of absolute and social space to put forth ideas about place and space in gaming. Nitsche states that “video games are social spaces understood as ‘narrative landscapes.’” What Nitsche is trying to say here is that gamers create their own sense of place through their interactions with virtual space. These interactions create a narrative unique to that player.

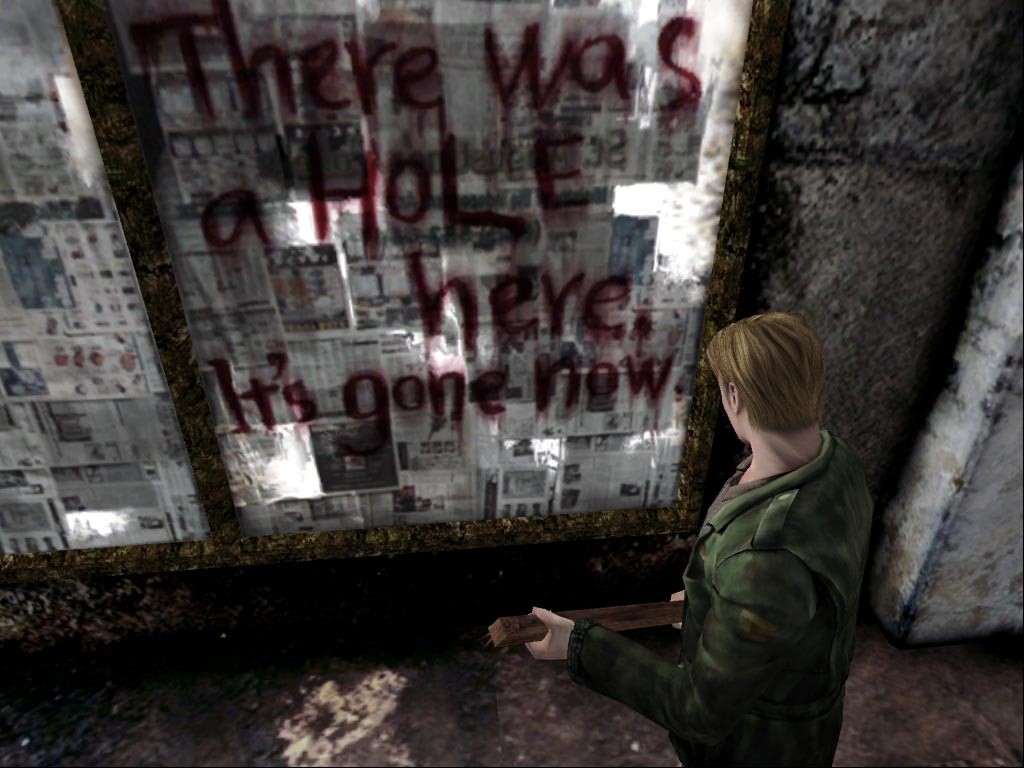

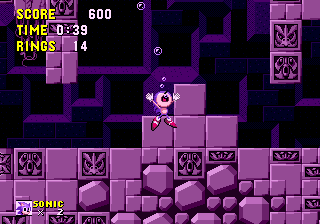

An example of a video game with a excellent sense of place can be found in Silent Hill 2. Silent Hill 2 is a psychological horror game released by Konami in 2001. The game centered on the protagonist James and his journey through the town of Silent Hill in search of his dead wife. Silent Hill 2 is not a sequel to the first Silent Hill however it does take place in the same foreboding town. Silent Hill as a series is praised for its attention to atmosphere and sound design. Instead of relying on jump scares, the games create a tense landscape often shrouded in fog. When inside of buildings, more often than not, the players view is intentionally made poor by the use of lighting and camera angles. The poor visibility, sound design, and enemy design make for an interesting way of navigating the games geography. For example, the camera angle when entering a room might show two corners of the room but leave two corners obscured. This instills a feeling of paranoia in the player as he or she is unable to check the area for enemies without being fully immersed in potential danger. The players radio will emit static when enemies are nearby, transforming the virtual landscape into an auditory one rather than a visual one. The radio forces players into a very primal state, where the player is using his or her sense of sound equally or even more than his or her sense of sight.

Additionally, the given historical significance of Silent Hill emphasizes sense of place as well. The town is very open to exploration and the player is encourage to form a relationship with it through his or her interactions with the simulated environment. This is an excellent example of a narrative landscape. In Silent Hill 2 (or any Silent Hill for that matter) many locations featured in the town can be revisited, and this adds a level of immersion for the player.

Additionally, the given historical significance of Silent Hill emphasizes sense of place as well. The town is very open to exploration and the player is encourage to form a relationship with it through his or her interactions with the simulated environment. This is an excellent example of a narrative landscape. In Silent Hill 2 (or any Silent Hill for that matter) many locations featured in the town can be revisited, and this adds a level of immersion for the player.

As demonstrated by the previous example, effective use of sound in a video game can enhance the player’s sense of plays immeasurably. In terms of geography, sound is a key element when attempting to experience a place, or a space for that matter. O’Donnel argues that “the ear never blinks.” This means that we are constantly listening, and cannot turn off our sense of sound as we can with our sense of sight. Sound plays an instrumental role in video games despite the commonly held thought that they are an exclusively visual form of media. According to Nitsche, video games rely on four types of sound to achieve immersion: sound effects, music, speech and soundscapes. Acoustic landmarks encourages sense of place by orienting the player within the soundscape. Sounds hep the player form a mental map in addition to the in-game map by orienting the player within the virtual place.

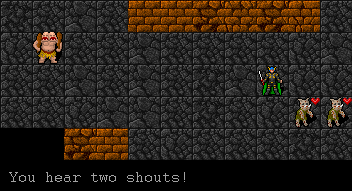

A game with a truly unique use of sound, Siren is a 2003 horror game developed by some of Silent Hill’s original team. The most important aspect of this game is a skill called “sightjackjng” in which the player navigates static attempting to see through the eyes of the enemies. Not only is the use of sound key in navigating the static, the ability wouldn’t be able to work without it as the static gets louder when the player is closer to sightjacking an enemy. The player has a map, but most of his or her navigation is guided by sightjacking. While an enemy is sightjacked, the player is able to see that enemies field of vision, as well as its location and the location of any enemies seen by the sightjacked enemy. In addition to the sound used when sighjacking, the music, sound effects, and speech of the enemies (if it can even be called speech) makes for a truly terrifying experience.

A game with a truly unique use of sound, Siren is a 2003 horror game developed by some of Silent Hill’s original team. The most important aspect of this game is a skill called “sightjackjng” in which the player navigates static attempting to see through the eyes of the enemies. Not only is the use of sound key in navigating the static, the ability wouldn’t be able to work without it as the static gets louder when the player is closer to sightjacking an enemy. The player has a map, but most of his or her navigation is guided by sightjacking. While an enemy is sightjacked, the player is able to see that enemies field of vision, as well as its location and the location of any enemies seen by the sightjacked enemy. In addition to the sound used when sighjacking, the music, sound effects, and speech of the enemies (if it can even be called speech) makes for a truly terrifying experience.

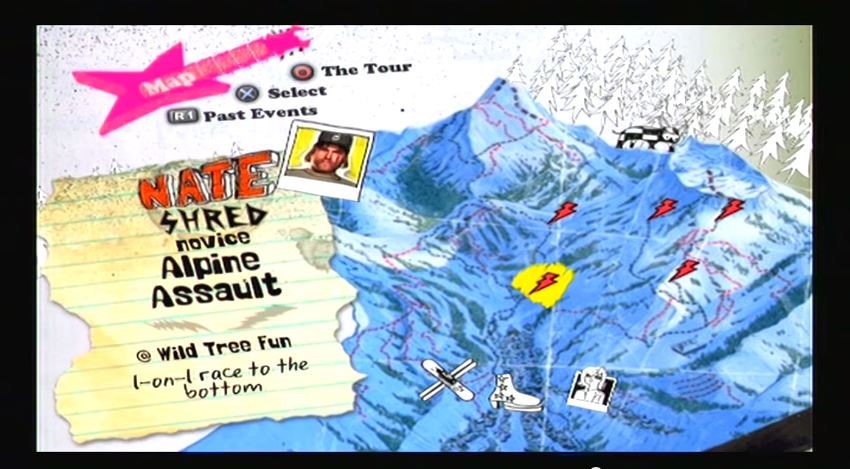

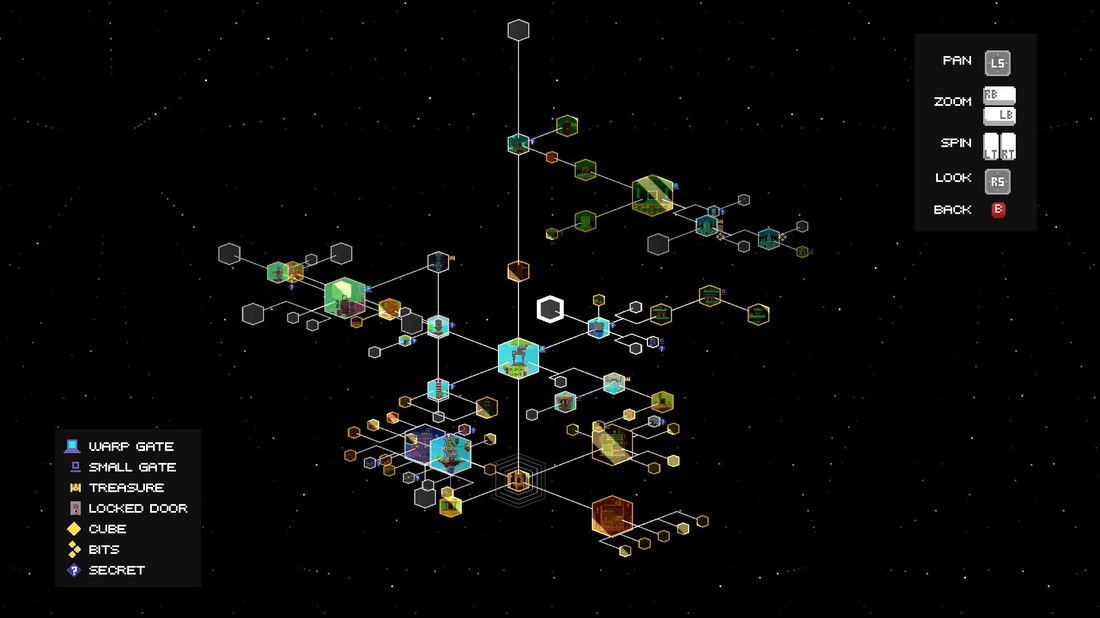

Maps are important when trying to navigate any place, virtual or otherwise. The player’s mental map can be extremely different from an in-game map, however both are used to orient the player. An interesting example of a video game map can be seen in SSX: On Tour. On Tour is a 2005 snowboarding and skiing game released by EA. The virtual mountain has no limits until you reach the bottom, and an average ride down the whole mountain takes at least 20 minutes. There is no in-game map, however the player does select events to participate in from a map of the slopes. What is interesting is that this map somehow effectively represents a 3-dimensional mountain on a 2-dimensional plane. Navigation in-game doesn’t rely on maps, but the player recognizes landmarks in relation to the event map, despite it looking nothing like the mountain.

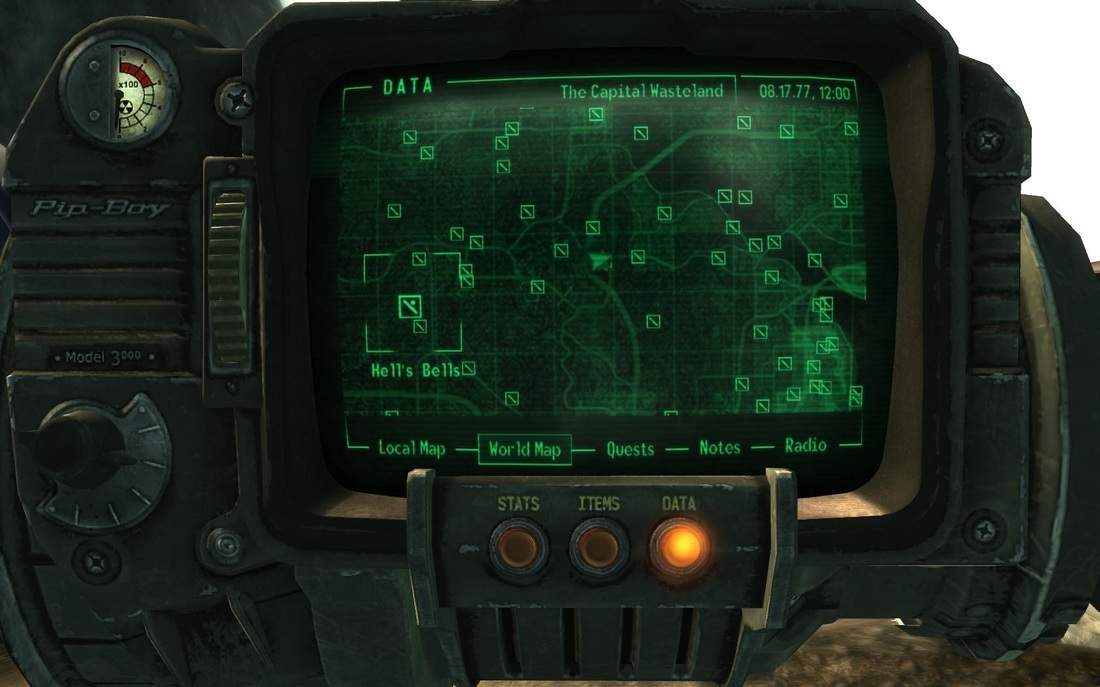

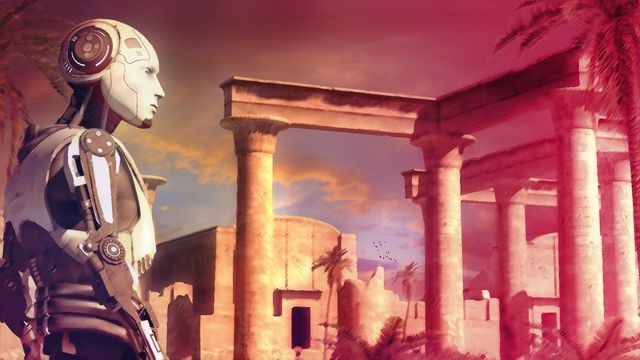

Finally, Red Faction Guerilla is a 2009 third-person shooter set on Mars with an emphasis on destruction. Players are given an arsenal of mining tools and weapons to fight, however the main point of this game is it’s incredibly fluid destruction engine. Every structure in the game can be destroyed, altering the landscape drastically. Buildings fall apart naturally; the player can destroy the supports or pick and choose what part of the structure to destroy. This game really plays with space in the sense that, once structures are destroyed there is no longer an enclosed space to orient yourself in. The player could make the entire planet open air, with the only space left being the natural landscape. While this games destruction engine is impressive, the game lacks a strong sense of place for this reason. Everything can be destroyed, so nothing is of value (with the exception of safehouses). Whether or not this is a good thing is for the player to decide.

How we experience space and place is dependant on many factors, some of which can be difficult to translate into games. When a sense of place is achieved, it utilizes geographical concepts to mediate the game world to the player. These can take the form of sound, space and place. Maps can also be integral in understanding virtual space, or as demonstrated above simply used as a reference for landmarks. While the player ultimately decides if a game is good or not is mainly their choice, however there is no denying that games have standards to be met. How the virtual world of the game is understood by the player is what truly makes a game successful.

-Nainoa Kalaukoa

How we experience space and place is dependant on many factors, some of which can be difficult to translate into games. When a sense of place is achieved, it utilizes geographical concepts to mediate the game world to the player. These can take the form of sound, space and place. Maps can also be integral in understanding virtual space, or as demonstrated above simply used as a reference for landmarks. While the player ultimately decides if a game is good or not is mainly their choice, however there is no denying that games have standards to be met. How the virtual world of the game is understood by the player is what truly makes a game successful.

-Nainoa Kalaukoa

Works Cited

1. Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2004. Print.

2. Nitsche, Michael. Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Game Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2008. Print.

1. Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2004. Print.

2. Nitsche, Michael. Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Game Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2008. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed